3 days ago

21 February 2012

#5 of 2012: Martha Marcy May Marlene

"Martha Marcy May Marlene" begins as the story of a victim's escape from an ongoing traumatic experience. As more and more information about that experience arises, interspersed with the circumstances of what is purported to be Martha's "recovery", it is clear that the film means to draw comparisons between two kinds of coercion: the kind imposed by a single charismatic leader on a small group of followers, and a traditional culture-wide adherence to self-damaging social behaviors/norms/values/aspirations. In that enterprise, it is disturbingly successful.

Before I get into the spoiler part of this, I'll start with my favorite visual/aural metaphor from the movie: the crystal clear-looking muffled conversation. On one of the first days Martha spends at her sister's lakehouse, her brother-in-law takes her out on their speedboat. They have some beers, it's a little tense, and then he offers to show her how to drive the boat. Their speech is all but completely drowned out by the motor, and on this sunny day out on the lake, the fact that their "conversation" can be heard but not understood seems to point to a distance not only between us and them, but between him and her. A second instance echoes this device: while cleaning the outside of a window (with the camera looking at them from inside), Martha and her sister have a disagreement. They can be heard, but the obstacle of the glass is prominent, and again seems to symbolize the near-invisible but blatant barrier to communication between characters. The beautiful view is the prioritized product of interactions in Lucy's domain.

Some of the first flashbacks of Martha's life on a rural commune inform the viewer that shortly after her arrival she was raped by the make-shift "family's" patriarch, Patrick, and subsequently told by female companions (especially handler and supposed friend Zoe) that this "first night" is a necessary, cleansing, joyous occasion which they had also experienced. Once Martha has become a full member of the "family", we get her access to the administration of the commune's goings-on. This is how we find out that the women not only counsel initiates after they are sexually abused, but also prepare them to be abused, both by drugging them beforehand and by characterizing the impending ritual as a mark of membership in the community ("We've all done it so there's nothing to worry about," Martha tells her charge). The idea of community-supported rape is a horrifying concept that, through the use of non-chronological flashbacks to tell the story of Martha's commune life, becomes buried deeper and deeper under a mountain of more subtle manipulations, including the changing of women's names. We see Martha playfully rechristened Marcy May by Patrick, then everyone actually begins to call her Marcy. Later, in an almost-missable moment, he is introduced to the first girl Martha gets to guide: "Have you met Sarah?" Zoe asks, and with a huge smile he says "Sally" (at this point, I started to wonder what name Zoe was a replacement for). From his first appearance on, Patrick is full of what could either be scattershot assumptions or educated guesses about Martha's emotional history that nonetheless hit their mark. Add that to his pseudo-philosophical apologetics and weird winsomeness, you have a classic cult leader. But this cult is mostly just a commune. Take out the extremely troubling "first night" that the women go through and the occasional breaking-and-entering (explained through political theory but primarily a mode of putting cash at Patrick's disposal), and the whole thing is like a weird hybrid: conservative rural American gender norms and livelihoods, paired with back-to-the-land anti-materialism. It's a functioning micro-society on some levels, even though the laws are set by a master opportunist who is also a terrifying presence.

The film's chronological backbone is "the present", as estranged-elder-sister-turned-rescuer Lucy tries to provide a place for Martha to rest until she "gets on her feet". Problems surface as the depth of the younger sibling's psychological trauma- revealed to the viewer though abrupt flashbacks during conversations, swimming, and sleep, and through behaviors that the camera observes Martha actively covering up- remains basically invisible to Lucy. Though their family history is largely left undisclosed, conversations before and at dinner give a few glimpses into the sisters' antagonism. First, out on the steps, the stark contrast between Lucy's polished politeness (while expressing a socially acceptable regret at not having been a better sister, among other things) and Martha's grasping frustration provides a hint as to why she ended up searching for an alternate family. Then, while eating, Lucy's husband provokes a discussion about "goals and expectations". He plays the "model acquisitive creative professional" with the attendant ideals about success and responsibility, and Martha plays the "radical anti-capitalist Walden-loving youth", and they both make some good points, until the whole thing devolves into a shouting match during which Martha vehemently defends the better parts of the life she has just left (while spewing some suspicious slogans) in the face of "traditional", somewhat repulsive, work-a-holic, moving-on-up type convictions. After a few more awkward days of existing nervously around the house, Martha's fear that her commune family may come after her overtakes her. While houseparty guests mingle, she becomes frightened and is whisked away to a bedroom where she is given a pill that looks and works very much like the one she had helped grind into Sarah's "first night" drink. After a few more awkward days, Lucy's husband attempts to wake a couch-sleeping Martha up in the middle of the night by (inappropriately?) touching her thigh. Confused, she flails and runs. For some reason he chases her very closely (what is he trying to do??) and she fends him off by kicking him down some stairs. At this point Lucy shows up, gets emotional, and expresses her desire to be left alone to complete her perfectly designed life without the threat Martha might pose to her as-yet-unconceived future child (which she later apologizes for), and Martha makes the brutally honest observation that Lucy will make a terrible mother (which she does not later apologize for). This completes the picture of their relationship for the viewer. While it doesn't make returning to the outright abuse and subtle mind-control at the commune seem like a great idea, Martha's "rescue" doesn't offer her a life that she fits into.

Thankfully, these aren't the only two options for most people, or even for Martha, probably (though who knows, in the end). What "Martha Marcy May Marlene" achieves by showing them intercut with eachother is recognition of the important fact that bad situations don't always look bad, that deep dysfunction might take some effort to uncover. A "normal life" isn't necessarily more healthy than a "crazy life".

28 October 2011

#103 of 2011: Take Shelter

my motivation to see this movie came largely from my love of/current inability to witness thunderstorms, since i come from storms and now live in a weak, persistent drizzle. my anticipation was further strengthened by the other imagery included in the trailer (weightless livingrooms, birdclouds), the promises of which are gorgeously kept by the film's dream/hallucination sequences.

my motivation to see this movie came largely from my love of/current inability to witness thunderstorms, since i come from storms and now live in a weak, persistent drizzle. my anticipation was further strengthened by the other imagery included in the trailer (weightless livingrooms, birdclouds), the promises of which are gorgeously kept by the film's dream/hallucination sequences. most of the film's other visuals are appropriately kept clean and naturalistic in the way that is comfortable enough to keep a viewer listening to the dialogue (which, in this case, is where most of the character development is stored) instead of continually ogling the scenery. after all, the film's emotional resonance is what makes it extraordinary, and that comes from the combination of personality-dense line delivery and the main character's thoughtful-though-sometimes-stunted process of trying to figure himself out. the aesthetics are simply the device by which the audience is reminded of the overwhelming bigness that our minds contain- successfully, if we're lucky.

18 July 2011

#69 of 2011: Birth

Only extraordinarily focused storytelling can make a viewer feel so strongly about the emotions of characters who she knows almost nothing about and who she has no reason to particularly like. "Birth" never gets off topic, except for temporary indulgences in pure contemplation of the setting (that dining room, my god). Even then, the small, overpatterned, overlush rooms of Anna's apartment- rarely without a preponderance of visitors, supposedly still at their ten-years-long work of stabilizing Anna's emotions- are a physical reminder of the overwhelming density of the simple storyline.

Only extraordinarily focused storytelling can make a viewer feel so strongly about the emotions of characters who she knows almost nothing about and who she has no reason to particularly like. "Birth" never gets off topic, except for temporary indulgences in pure contemplation of the setting (that dining room, my god). Even then, the small, overpatterned, overlush rooms of Anna's apartment- rarely without a preponderance of visitors, supposedly still at their ten-years-long work of stabilizing Anna's emotions- are a physical reminder of the overwhelming density of the simple storyline.It's important to note how huge a role omission plays in the film's poignancy. The decision to represent the original Sean minimally (with only an imageless voiceover at the opening of the film, followed by a faceless body running through the snow for 2.5 minutes before succumbing matter-of-factly to a heart attack) lays the foundation for the tense and unresolvable ambiguity about whether or not something paranormal is at work: we have to take most of our cues from Anna, because we can't compare the dead Sean to the boy Sean, played by Cameron Bright. The latter's performance is, itself, a kind of fillable blank- slow, deliberate, contemplative, cryptic. When he's on screen with Nicole Kidman's Anna (an irreparably affected woman whose apparent brokenness seems more and more to come from a well of deluded commitment to an ideal that probably never existed in the first place), it's almost as if we can see the clean slate of his nearly expressionless face and tone of voice being filled in by her desperation for the love she thought was hers when her husband was alive.

Another omission: answers. As always, I was perfectly happy to find no clean explanation for the mentally fatiguing ordeal that both main characters (and viewers, too) experience due to this plot. Hard facts are of negligible importance by the end of the film, if they were ever important at all.

Oh yea, and Lauren Bacall is the matriarch.

27 May 2011

#57 of 2011: Dogtooth

the first thing i want to say has something to do with how absorptive this film is considering its 'bareness' and its peculiar premise. on some sort of coordinate plane with axes for viewer investment and narrative complexity and perceived production cost, "Dogtooth" would share a pushpin with Michael Haneke's films: it is a seemingly natural, straightforward location inhabited by a few important characters who interact in consistently compelling ways, as dictated by a story that is told enough to keep the viewer rapt without excessively defending its own probability.

as for acting: Christos Stergioglou as the dad is a paradigm tyrant, but Aggeliki Papoulia and Mary Tsoni as the daughters are especially impossible to stop watching. their dancing, their playing, their conversation (they are the only characters in the film between whom there is neither significant antagonism nor stifling distance), and their violations of the family's codes introduce a measure of doubt into attempts by the viewer to judge their situation. is it an unsustainable paradise which the facts of nature will not allow to persist? or is it an idyllic prison where they are unwitting (at least for the earlier bulk of their lives) victims whose right it is to escape? by the end of the film, this issue is cleared up, but- meaningfully- it is impossible to tell if the decisive factor originates inside or outside the house.

on the imagery front, nearly every shot is brimming with contradiction: appalling but comically absurd (father beating progeny with videocassette contraband which he has securely taped to his own hand), awkward and ravishing (the anniversary dance), violently chaotic while at the same time painterly (see below).

26 May 2011

#55 of 2011: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

as i become familiar with the work of the Coen Bros, they remind me more of Woody Allen in this way: i see what's going on in terms of style, and it is interesting (even astounding at particular moments), though as a whole, the thing doesn't shake me much. that said, it has to be acknowledged that with the Coens, specific triumphs (in narrative or character development or imagery) are often redemptive of the entire undertaking.

but first: a significant drawback. George Clooney's performance was possibly the most under-realized aspect of this movie, with the most obvious shortcoming being his line delivery- both his timing and his accent. i understand that his character is supposed to be a fast/sharp/smooth talker, so it makes sense for the audience to note a distinction between his speech and the drawls of his companions. but it becomes too obvious that he's half-assing when even John Goodman's minor character (also a salesman, and apparently a better one) sounds more authentic. and next to the measured and involved facial expressions and diction of Turturro and Nelson, Clooney simply comes off as unimpressive (instead of "faux impressive", as the writing seems to demand). Turturro and Nelson pull off the stylized melodrama with their typical comedic flair, especially when it's a tad corny. if Clooney weren't capable of doing the same, i might not feel so slighted. but that's what i get for watching "O Brother" after seeing "Burn After Reading". maybe he just needed time to learn.

now for the redemption: 1:09:03-1:09:21. i'm not sure if Roger Deakins or the Bros deserve the greater portion of credit for this, but it's a striking use of three things as simple as darkness, flashes of colored light, and camera movement (RESOURCEFUL EFFECTS. YES.).

what makes this different from other "camera descends into the narrative" scenes is its expertly nuanced balance between expressionism (dream sequence) and naturalism (scenery description). the camera pans down slowly while artificial blue flashes illuminate a branch so that it resembles the represented source of light. but the contrast is absolute between the black and the branch, and the flashes are short-lived and sparse, so that when a noose moves through the frame, it is logical to assume that what is being shown is simply a tree that has been prepared for a hanging. . . except that the darkness that follows the noose's appearance is invaded by an interior scene, with the camera continuing it's journey until it lands on a terrified John Turturro. it wouldn't make sense for a noose to be hanging above this building, and (because the panning had til now made sense) this is a bit jarring for the duration of the time it takes the camera to scan the room, from its rafters down to the bunks of sleeping men. by the moment movement ceases, by the time Turturro- awake amongst sleepers- fills the frame, the previous two images register not only as a combination that actually exists within the world of the story, but also as stark and terrifying fragments of a dream that has shaken this man awake. the camera's continued motion stitches everything together, paces the experience of the viewer in such a way that s/he and the character simultaneously "wake up". and it is good enough to recommend.

03 February 2011

#107 of 2010: A Woman is A Woman

i don't have much of a desire to review Godard. that's not really an option based on how/why i watch his movies. and how/why is that? by making/to make a list, as follows:

emile (Jean-Claude Brialy): "why are you crying?"

angela (Anna Karina): "because i wish i could be both little yellow animals at the same time."

emile: "you always want the impossible."

angela: *smile*

angela says a general, contentedly-affirming-but-overall-emotionally-neutral thing in response to alfred's (Jean-Paul Belmondo) request to hear her thoughts and then she walks across the street away from the camera. he turns to the camera with his cigarette dangling out his mouth, says, "and off she goes," then turns away to watch her as the focus drifts up to the neon sign on the building.

alfred: "i'm very clever."

angela: "oh really? bet you can't do everything i can."

alfred: "bet i can"

several shots of them standing in identical poses, revealed in the last shot to have been angela's plot to get alfred back for slapping her ass by kicking his.

angela: "could you sweep the floor instead of acting like a jerk"

emile stops at the window and turns, the camera traces his sight line as the words "EMILE TAKES ANGELA LITERALLY BECAUSE HE LOVES HER" appear one by one across the screen, then disappear. the camera reaches her, she stands, and the camera pans back, a stare volley, while "AND ANGELA CAN'T BACK DOWN BECAUSE SHE LOVES HIM" appears last word to first word in a right to left progression.

after a little spikey speech back and forth, they both look down and then look up at some off center focal point, the camera starts a slow rotation leftwards, towards the door, and another sentence appears a few words at a time, backwards as the one about angela had: "BECAUSE THEY LOVE EACH OTHER EVERYTHING WILL GO WRONG FOR EMILE AND ANGELA". stops. volleys back to the couple with: "THEY MISTAKENLY THINK THEY CAN CROSS THE LIMITS DUE TO THEIR MUTUAL UNDYING LOVE".

alfred (Belmondo) says "make up your minds, Breathless is on tv and i don't want to miss it"

the boys whisper to each other and laugh, suddenly allied against angela's toying with them. somehow incredibly precious. everyone is on a schoolyard in demeanor.

woman: "they're showing vera cruz"

alfred: "my pal burt lancaster is in it" (turns to the camera, grits teeth in a Lancaster Grin)

angela flips an egg into the air, runs next door to answer the phone, asks alfred to hold on, runs back in her apartment, catches the egg.

happy ending with forgiveness and books and sex and Anna Karina winks at the camera.

31 January 2011

#106 of 2010: ...And God Created Woman

of all the movies i watched in 2010, this is the one from which i took the largest number of screen shots. the preponderance of camera setup/camera motion tics in ...And God Created Woman was unignorable. for instance, check out the "large dark visual metaphor for emotional distance hogging up a significant portion of the frame" trick:

zooming in and zooming out to indicate trouble for the sensitive young bro with a soulful nymph wife (who has not-so secret and not-so unfulfilled longings for older bro) is another common occurrence in the film, as seen here:

i don't have any shots of what was probably the most moving scene (fittingly the near-tragic violent climax). certainly i was too transfixed by Ms. Bardot's impassioned, solitary dancing to interrupt. instead of reading me ramble on about how refreshing it was to see a smoking hot young woman embrace her sensuality for the pure pleasure of it (rather than as a bargaining chip in the business of life), just watch this movie.

#105 of 2010: Casino

obvious compare/contrast-type statements: more Robert Deniro, a more convoluted relationship storyline, and a more graphic whacking of Joe Pesci's character (Nicky in this case) than we saw in Goodfellas.

now for what really sticks with me about this movie.

a subtle but important triumph of Casino is how effectively it utilizes voiceover. the entire film is narrated by the two main characters alternately, but there are two places where a disembodied voice plays an especially captivating/surprising role in the transpiration of a scene.

the first of these occurs around the 43:00 mark. it's the night of Ace and Ginger's wedding, and as she sits in the hallway outside of the reception, on the telephone with Lester (her slimy, unshakable emotional baggage personified), we see Ace come through the door to find her [Lester's voice: "this is great for us"]. cut to a reverse shot of what Ace sees: his new wife, the hitherto strong, charming, smart hustler with whom he has basically cut a deal in the hopes that they can have what they need from each other, now slouched, crying, clinging to a payphone outside her own wedding reception. just as the shot reverses to show us Ace's reaction to all this, Lester's voice continues, "I'm looking at you right now. I'm seeing you for the very first time, right this minute." Lester's creepy/nostalgic/manipulative remembrances of the Ginger he met when she was just 14 occur on the soundtrack simultaneously with Ace's first unavoidable glimpse into her past, his first real encounter with the side of Ginger that is still as malleable and scared and frail as if she were fresh on the street. we were already pretty sure that his willful ignorance and exaggerated sense of control were going to cause him trouble. now he's starting to see it that way, too.

the second striking voiceover comes at about 2:47:30, ten minutes shy of the credits. Nicky has gotten a big head, messed around, fouled up. and though Ace's narration clues us in on what's about to happen out in the cornfield, Nicky's voice reassures us that he organized this meeting, that he's gonna straighten things out, that he wants to make sure his "brother don't get fucked around. what's right is right. they don't give a fuck abou- AGGH!". the voiceover is cut short by a baseball bat to the back; the flashback catches up with the narration. it's a bit of a brainmess, sort of a paradox, but it is also effective. even the source of approximately half of the story can wind up beaten and buried still breathing alongside his brother in a cornfield. even a "made" narrator isn't safe.

and this line about Piscano: "this guy, basically, sunk the whole world". it's a good line.

Casino is tragic in the way that you see coming right from the beginning, but it makes sure to take you along for the ride. nifty camera manipulations. pretty splendid performances. worth recommending.

25 September 2010

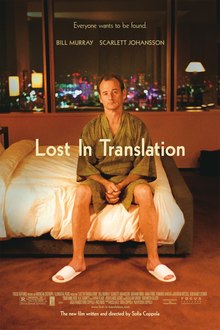

#104 of 2010: Lost in Translation

Movies like this don't seem like they need me to say much about them. First, because so many people have seen them and have already said plenty about them, and second, because you should probably just watch them if you haven't already. (I'm not saying that I write extensively about movies like Fassbinder's "Lola" because they need me to talk about them, or haven't been widely seen. You know what I mean.)

One gripe: the "ahh-ahhh oooo-ooo ah oh aaahhh" music was a little much at times, particularly when Bill Murray gets to Tokyo. that should have been like, a pared-down cello, you know. but luckily that scene is fairly generic and I don't recall crappy sounds ruining any of the outstanding scenes.

It has been noted by plenty of critics, and I agree, that one of the most profound accomplishments of the story is that its "romance-without-sex"-ness doesn't come off as stifled or repressed (as if by wrong-headed 'morals'). The situation speaks clearly (almost startlingly) to the "issue"/odyssey/wonder that is friendship between supposed sexual counterparts, and it effectively and movingly challenges some very ingrained (though, thankfully, often questioned) notions about the kinds of relationships between men and women that might be considered "fulfilling". It doesn't make up our minds for us, either, doesn't tell us how wrong or right traditional wisdom is. The brief and inconclusive introductions of so many important factors help the Bill/Scarlett interaction to seem more like real life- where you can never quite say for sure- than a sermon on gender relations. If you haven't seen it yet, go ahead, it's "highly recommended" for being highly watchable.

#103 of 2010: Multiplicity

I'm not kidding. Jmilz told me she wanted a review on the little cinematic gem that is "Multiplicity", and I aim to please with this blog. Obviously.

First observation: Micheal Keaton is not a "good actor". He falls somewhere between Kevin Costner and Nicolas Cage, almost as if he is, himself, the outcome of some hollywood genetic accident where the test tube "Cage's spaziness and gravel-whisper voice" got dumped into "Costner's bland looks and latent pattern baldness" and some kind of full grown baby happened, complete with plaid workshirt. Second observation: Micheal Keaton is impossibly hilarious in th(i/e)s(e) role(s).

The clones are easy, middle-school skit character sketches: Tough Guy, Effeminate Man, and The Idiot. But that sort of works here: in a movie about how what seems like a simple solution (and is treated in passing conversational hyperbole as one, which was undoubtedly the inspiration for this story in the first place) is actually a complex mix of drawbacks and advantages, it makes sense to take the three extremes of what men are and turn them into simple characters who interact externally in representations of the complex ways we all deal with our own facets, our own "versions" of ourselves. Ok, maybe that's a bit of a stretch, considering how much time is frittered away on the "I'm The Only One Who Sleeps With My Wife" rule and the instances of its being "bent" or "broken". That's not exactly a literal illustration of deep, metaphorical, existential quandaries (or. . .?).

Andie McDowell is delicate and lovely in a "normalish southern person with a perm" kind of way. It's a little sad that a movie that was made in 1996 treats the "working mom" thing as a MAJOR plot thickener, but I guess there are still, to this day, women dealing with that shit. As funny as Michael Keaton's character might be, he's also a totally self-involved asswipe. And maybe it's a bit problematic that what seems to be a marriage-breaking disconnect (in two ways: 1] to her, he appears to be erratic, unstable, and sometimes completely unresponsive to her based on which clone is standing in, and 2] even WORSE than the problems she perceives, he's actually OFF SAILING while instructing the stand-ins not to take any of the privileges of emotional intimacy even if they are the ones actually experiencing it and putting in the effort to achieve it, because he certainly isn't) is absolved with the expensive and time-consuming remodel of the kitchen. Well and I guess he promises to be a better husband, or something. Ok, sure.

I'm gonna slap a "recommended" on this, you know, why not. Plus Laszlo Kovacs as DoP?!

09 September 2010

#102 of 2010: Goodfellas

There were some great slo-mos, a gripping freeze frame at the instant of a firing gun's flare, and that CLASSIC zoom in/dolly out in the cafe. I wasn't so thrilled about Karen's freaking out voice, and I definitely thought that allowing her to narrate just for that little bit was detrimental to the effectiveness of the narration device as a whole. costuming was really notable, especially the outfit Henry wears as he beats the shit out of Karen's neighbor. There's more to say, clearly, but I'm making an effort to catch back up on these reviews. Recommend.

08 September 2010

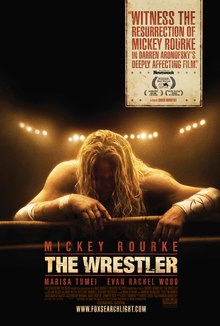

#101 of 2010: The Wrestler

"The Wrestler" is punishing on several levels. It wraps up all the down(est)sides of everything from hero worship to commercialized body image to absentee fatherhood to nostalgia for the eighties (and the list goes on), while still getting viewers to care about what is happening to the characters (a point where that other Aronofsky adaptation, "Requiem for a Dream", largely failed, in my opinion). Mickey Rourke: yes. Marisa Tomei: yea, alright. Evan Rachel Wood: maybe not. The daughter storyline is to be expected. Of course this torn up old beast of a man fathered a child twentysome years ago (right?). But I feel like this aspect of the plot gets severely boiled down and serves (a little too exclusively) as an excuse for Randy to get to know the "Pam" side of "Cassidy". Which, cool, "we both have kids and shit, we both work in entertainment industries but are real people, look at us, we're real, but one of us definitely feels more real when we're working". And it's the super tan bleach blonde one. . . the man, the legend, the Ram. Cut to final RAM JAM. The End. I may have been too hard on "The Wrestler"'s narrative oomph, because immediately after I saw it, I watched "Goodfellas" for the first time, and of the two the latter stands out a bit more prominently in my mind. I still recommend the former, especially if you are into "walking in ____'s shoes" downers.

#100 of 2010: Paris, Texas

The incredibly slow trickle of narrative disclosure made the first hour of "Paris, Texas" a little tough to get through, but after all is said and done, I think the pacing of the film can be considered one of its most notable achievements. It starts out a garble that we see through "the brother's" eyes, and the tension of what will happen if or when Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) comes back into the life of his son, Hunter, competently propels the garble on through the first forty minutes. By the time Hunter says "Goodnight, Dad" twice, I began to wonder if there was any story left to tell. Or rather, I knew there was story left to tell, but judging from the opening half of the movie, I had my doubts as to whether or not it would get told. At precisely 1:02:01, everything starts all over again, with the simple gesture of walking backwards on the other side of the street. From this point on, I was enamored. The remainder is speckled with little vignettes that keep you watching and listening- fully attentive to what is being shown and said- because your brain figured out early on that here, there's no reward for guesswork.

One of my favorite scenes was the one on the bridge. On first viewing, it seemed completely interruptive (i didn't mind), and now that I skim it again, I see the significance in showing Travis walking at night, then cutting to him walking (in the same direction) across a bridge over some highway in the low light of what could easily be taken for early morning: after learning that there might be a way for him to find his long-lost wife, he walks all night, quickly, without giving much notice to his environment. Still, it isn't the narrative implications that get me about this scene. It's the way the sound (an audio parfait of footsteps and traffic buzz and some echo-y orating within the scene, topped off with that bending and twanging guitar soundtrack) and the visual composition (tracking Travis, who's centered in the shot, as he glides over the bi-directional river of head- and tail-lights) combine and fluctuate and culminate in Travis slowing down as the shot overtakes the orator (who turns toward him without lowering his volume), and the guitar drops back while we listen (along with our main character) about how "none of that area will be called a safety zone. there will be no safety zone. i can guarantee you the safety zone will be eliminated. eradicated." The orator turns back towards the highway, Travis softly touches his back as he walks around him, and the camera let's our main character walk on without it.

ps, Hunter is great. Not like a "great kid actor", but a real kid who doesn't seem like he's on film.

06 September 2010

#99 of 2010: Hara Kiri

In the tradition of non linear storytelling, "Hara Kiri" calls into question the efficacy of first impressions and, in the process, also casts doubt on the morality of strictly defining what kinds of behavior count as"honorable". Most of the film is fairly understated, but moments of tension (i.e. are they gonna make him stab himself with a bamboo blade?) are furiously anxious, and the quiet sadness of Tatsuya Nakadai's character is absolute.

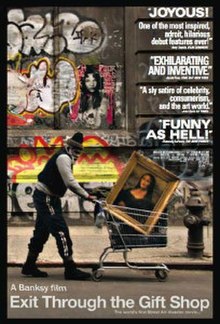

#98 of 2010: Exit Through the Gift Shop

Some of the dialogue/monologue is hilarious, but the "this guy is a schlub" shtick begins to breach overkill right around the time that Banksy starts to really paint himself as the genuine article/overlord/golden standard of socially integrated art-making. Maybe he is, and I don't care to get into that, I just wish that he would have allowed some of the criticism of his modus operandi/aesthetic to fall on his own shoulders instead of re-routing the whole deluge of "can you really call this guy an artist and sell his work as art" in "Mr. Brainwash"'s bumbling direction (and setting up a pretty clear analogy to a certain Mr. Hirst). I really enjoyed the scene with the "forged" currency, how in the end, anonymity or not, the artist knows that there are limits, that you can't just do ANYTHING and still expect to work and make an impact, and I wish there would have been more of those "oops" moments, not just for comedic effect. As for the "hoax vs. docu" semi-controversy, I went into the viewing with the idea that the "real subject" was fictionalized, and I enjoyed the bulk of the movie from that angle. Overall I'll recommend it, especially for people (like me) who are unclear on the development of "street art" as a genre.

01 September 2010

#97 of 2010: Paper Moon

Maybe it's the fact that the biological relationship between the characters Addie and Moses is tenuous that allowed Tatum O'Neal to so totally break out of the shadow of being the male lead's daughter in real life. After all, this wasn't just a case of an actor parent supplying their own child to play their character's child. This isn't an easy case of "just act like i'm your dad, but in a different setting, and call me a different name". This is a real role, a lead role, really. But calling her a "supporting actress" allowed Ms. O'Neal to become the youngest person even to win an Oscar (she beat out her co-star Madeline Kahn's comedic performance for it). "Historical Awards Wins" and "Incredibly Young" aside, the younger O'Neal's gravelly voice and locked scowl, her androgynous grit and youth and supposed poverty of "sentiment", smoking in bed, scheming for affection, smarts, everything she is, down to how her hair is cut and how she walks (even in the dress she wanted but won't change for, she'll wear but won't inhabit, because her clothes don't make her), contributes to the beautifully filmed steely grey edge on everything. It's an edge made of a lot of dust but it's still reeeeal hard looking, which might be the only way to ensure the preservation of soft, old-fashioned fondness.

17 August 2010

#96 of 2010: Inception

"thought it would be all about the visual, but it's more about the feel of it" -ariadne (ellen page)

no, ms. architect. you are mistaken. any feeling that "Inception" conveys is built primarily on visuals. in fact, not just the feeling, but the meaning and the narrative of the film are rooted much more firmly in aesthetics than in verbal poetics or hard logic. and i don't have a problem with this, because it made for incredible watching. that "waking up from 50 yrs of fantasy building" bit, where marion cotillard suicidally contemplates a knife in front of a positively glowing red vegetable on a cutting board- simple, stunning photography. and the dream world training run with ariadne was like a wonderful over-the-top magic stage routine during which you forget to keep track of the performer's hands. most of the movie is like that, if "the performer's hands" is seen as a metaphor for "the meat and bones of the story". of course, i'm not willing to let everything slide for the sensuality of the movie. one thing that annoyed me was how the male team members had to rely almost entirely on their ethnicities and quickly exemplified "special abilities" to provide distinction amongst them. their personalities were all but nonexistent. another gripe was the undue portion of the weight of the story that seemed cast on ariadne "accidentally" forcing her way into cobb's unconscious. and seriously, "ariadne"? the lovely, smart female student who dresses almost exclusively in obvious layers is not only the architect entrusted to build the dream worlds, but also the guardian of cobb's fragile secret and basically broken emotional composure? *her namesake is the thread girl who helped the youths get out of the labyrinth? then i don't understand why whoever was in charge of the soundtrack didn't make sure to play "dream weaver" every time the camera (playing the p.o.v. of cobb) turns to her.

although this short version of a review seems to lean towards negative, i have no trouble at all recommending "Inception". it is, in general, a compelling film and a legendarily beautiful parade of images.

*i had ariadne and arachne confused. duuuh. but still. blatent mythology tie in to do with textile production.

13 August 2010

#95 of 2010: La Femme Nikita

see "B13" review regarding the characters and plots of Besson. Nikita was pretty dynamic, but still fit in to that description. there was a strangely relatable undercurrent throughout the whole thing relating to the helplessness of people trying to occupy their own lives despite the hellish trap of constant obligation. the love is jumped to in the story, but sincere feeling. the violence is not especially graphic, but in context it is disturbing and stripped of logic or explanation (as it probably should always be depicted). overall, she's not all laid out as a natural bad ass or a victim overcoming her trauma, she's pretty emotional and kind of quiet, and she's not a "nice girl". that's a protagonist that we don't often get to see in action films. also i was sad when victor died purely because of leon. recommend.

12 August 2010

#94 of 2010: Blackmail

billed as a thriller- and there were some suspenseful or downright thrilling parts- but more of a really really really dark comedy (no way that in any era all of those "knife gags" were intended to be straight scary). and intentional or not, it was a really good really really really dark comedy. recommended.

08 August 2010

#93 of 2010: B13

the script was fairly shallow, with the white, male, compassionate, heroic ass-kickers bringing it from both sides of the "tracks" (or wall) with wonderfully choreographed flair. as with several of mr. besson's film projects, the characters are fairly strong iterations of recognizable stereotypes, the underlying message is thought-provoking, and the outcome is warm and right, even though the situations sometimes skirt absurdity without fully embracing it (a dangerous place to be). i found the little sister's story undeniably lacking and hurried and flat where it could have either contributed or been left alone. but i'll recommend "B13" overall for the parkour and solid action storyline.

#92 of 2010: 10 Shorts by the Bros Quay

i couldn't stop writing while watching these. and "street of crocodiles" is perhaps the single most pressing motivation i can think of (ed's encouragement comes in at a close second) for me to make a film of my own (though it won't be animation). this short has been pivotal in my development of a more detailed and thought out theory of the ability of film to manipulate time like no other medium. and as much as i wish i had the focus and time to hash out everything i thought about even a single film in this collection (perhaps someday, after hundreds of viewings), i can't say anything other than find it and watch it.

#91 of 2010: Russian Ark

there were rembrandts. spectral guides. slices of history taken not from cultural climaxes or defining moments, but from the daily homelife of royals, the nondescript pain of common people, and the in-between and just-before moments that define a nation as much as the most recognizable pinpoints on timelines. the power of the film comes from the drifting, from the soundtrack that keeps the viewer uncomfortable, from the views, and from the feeling that we are actually stumbling- right along with the disembodied voice and his guide, the marquis- in and out of real history. "Russian Ark" is both breathtaking and subtle, incorporating the most intricate architecture and overdone period costume into a bare-bones non-narrative that pretty much amounts to a fantastically compelling and tantalizingly incomplete history lesson. sokurov has certainly made me crave information about Russia and renewed my desire to become more versed in general world history. major props to tillman buttner for his stamina and timing with the swooping pans.

#90 of 2010: Short Circuit

i thought i had seen this as a kid but i'd actually only seen "Short Circuit 2", which has the advantage of starring the most entertaining two characters (Johnny 5 and Ben) without the baggage of ally sheedy's horrible failing and painfully unnatural line delivery (disclaimer: i haven't seen the sequel since i was maybe 6 or 7, so i can't vouch for it really being good. i do remember a sweet scene in a bookstore or library where Johnny 5 devours all the books, which i have wished i could do ever since). the anti-military theme reminded me of "Real Genius", but with fewer academia-based hijinks and less concern for developing characters that a viewer can really give a shit about. still- somehow- "Short Circuit" managed to be surprisingly delightful. No. 5 was alive enough to make up for (almost) everyone else's glaring creative incompetence.

Labels:

80's,

ally sheedy,

american,

bad acting,

fisher stevens,

john badham,

recommended,

robot comedy,

science,

steve guttenberg

#89 of 2010: Five Easy Pieces

jack nicholson as Bobby claims to not feel anything but what that actually means is he feels a lot of shit and it doesn't feel nice because he's a total Guy In The Seventies and doesn't know how to balance doing "hard work" plus "having a good time" with being a sensitive pianist and a scared little boy on the inside. his well-to-do family of musicians include people who he generally ignores, though his sister is an incredible sweetheart (smart and a tad awkward, but full of feeling and good humor). strained relationships with dad and bro, no surprise there, and depictions of troubled masculinity throughout the movie- from the physical ailments of dad (stroke) and bro (some neck thing, now he can't play his violin), to the law hauling away Bobby's dim, giggling pal (who seems to represent self-satisfied, "settled down" blue collar america, the authentic version of what Bobby pretends to be). as the film's most prevalent on-screen plot complications (the family issues are established as having arisen before the time period which is the subject of the film) are Bobby's relationships with two different women (an emotionally dependent, intellectually simple, gaudily feminine pregnant waitress who is Bobby's mental inferior but moral superior; and a softspokenly delicate, independent fellow musician (and soon to be sister-in-law) who is Bobby's emotional superior and intellectual equal), it is important to note (and commend) the depth and variety of gender depictions presented in "Five Easy Pieces". overall, it seems like the women (sister, pregnant girlfriend, short-term love affair) come off as more stable, thoughful, compassionate, and rational people, though there are certainly negative female counterpoints (the "pompous celibate" and the almost intolerable [but hilarious] hitchhiker). the most likable male character is probably the nurse, who is little more than a hulking, whitewashed mass of comic relief and a chance for the sweetheart sister to demonstrate her full personhood through sexuality. i'd like to go on about the visuals, but i've spent so much time on the gender bit that all i'll say is: that bit after Bobby gets on a moving truck and plays piano up the exit ramp, the next scene, he's walking around in what basically looks like a George Segal from the late 60's/early 70's, and it is evocative in the same way, with the same economy of image and lack of (need for) verbal explanations. also, T. Bak pointed out to me the expressionist use of the oil derricks in the aforementioned run-in-with-the-law scene, which is a praise-worthy utilization (and transformation, from eyesore to emotional barometer) of that machine.

14 July 2010

#88 of 2010: Micmacs a Tire-Larigot

Some large, uncomfortable and unsightly stitches hold together the endlessly pleasing visual gags of "Micmacs" and the films fairly heavy (complete with close-ups of photos of war-mutilated children) anti-weaponry message. One of these stitches is a prolonged montage where the camera watches people watch YouTube and sometimes skips the people and watches YouTube directly. Like other reviewers of the film, I wouldn't have minded the romance between the comedian and the contortionist taking up a bit more screen time, but, "Amelie" this is not. In the end, the sight gags worked, and I liked the movie, holes, hasty sutures, and all.

#87 of 2010: Daisies

they giggle, maniacally; they're thin and peppy in swimsuits, dresses, heels; they'll hang out with a rich old dude for a meal and entertainment. but after they get bored of teasing and frolicking, they'll light wads of crepe paper on fire in their room and cut phallic foods (pickle, sausage, crescent roll, banana) into tiny pieces with scissors to the soundtrack of a lovesick butterfly collector on the phone.

it might be possible to miss the feminism of this film- the message isn't militant or presented in an altogether serious fashion- but you aren't watching very closely if you do. "Daisies" continuously points out contradictions in society's opinions on propriety and feminine behavior [example: stylized drunkeness and suggestive dancing by a couple performers doing a flapper number are enjoyed by a chuckling, clapping audience, but the crowd is completely indignant when the two girls get drunk and dance for real. ACTUALLY having fun instead of faking a good time is NOT ok].

far from being a manifesto, or even suggesting how things "should" be, Chytilova's attention-getting early feature film is an absurd/surreal interpretation of the current (as of the 60's, and we can argue how far we've come since then) state of womanhood, which was and still is rather absurd on its own. this is the point. it is made with joyous, psychedelic, and well-paced deftness. and you should watch it.

#86 of 2010: Forbidden Planet

Leslie Nielsen is totally being serious: there is some heavy shit going down on this planet. Oh but first we'd better make sure we decide who gets the sexy daughter. Ok, it's Leslie, NOW we can try to figure out what's up with people getting ripped apart by some huge, malicious, unconquerable force. This movie was made in 1956, and I'd be willing to bet that it inspired more than a few kitschy/futuristic mansions. Despite hindsight and shifts in decorating tastes, the film is a pretty incredible visual feat. Good source material, too. The action/suspense/thriller agenda moved out of the way to let a healthy portion (in 50's sci-fi terms) of epistemology and ethics come across at several points, and the solution to the "what's eating/disemboweling gilbert astronaut?" riddle is pretty smart and well explained, if not a total surprise by the time it's revealed. I feel like that kind of dramatic irony was more respected back then, the kind where you make the characters even more dumb than the viewer so as to appeal to a wider audience and make people feel special. Of course there are contemporary examples. Like in that fucking "Da Vinci Code" book when a professional cryptologist has to stare at a scrap of text for HOURS before he thinks to get out a mirror. Dude, it's the name of the book. Hint. Anyways, I recommend "The Forbidden Plant" for it's fully electronic musical score, it's well-developed hypothetical super-intelligent beings and explanation of human research of them, and images like this one:

10 July 2010

#85 of 2010: Freaks

I don't feel like I have to say a whole lot about "Freaks". Someone who was into the fantastic margins of culture- long before I had realized how huge the margins are- told me to watch it years ago, just like someone probably told you to watch it years ago, and if you haven't yet, do. Even as it puts the characters (who are largely identical to the actors who play them, melodramatic relationship crises aside) "on display", the film somehow manages to use the same voyeurism that allows the performers to earn a living as "sideshows" and "monstrosities" towards an opposing goal: it makes us wish that more people were like them. Because there would presumably be a whole lot less marginalization, mistreatment, and self-pity in the world if more people were as accepting, thoughtful, and resourceful as the "freaks" are here.

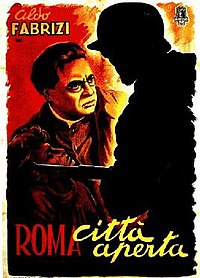

#84 of 2010: Rome, Open City

The setting (filming began only two months after the Nazis were driven from the country, the year after the story takes place) and concerns (with the responsibilities and risks, desires and decisions, the adaptability- for better or worse- of regular people in dire circumstances) of "Rome, Open City" are decidedly neorealist. Though not strictly faithful to that sub-genre, the scriptedness of Fellini's meticulous character development pairs wonderfully with the deft, professional, sincere, and sometimes even over-emotional (especially in Anna Magnini's case) acting, and the result is a perfectly distilled story with honest reality as a backdrop. As for the look of the film, Rossellini sure has an eye for composing a scene. Seen in context, after traveling through a story full of death-by-injustice, this final preparation is devastating:

As always, it is heart-rending to watch a truly good man (even a fictional one, though i'm sure the priest depicted here has historical counterparts) abruptly ceasing to exist at the hands of despicable forces. The visual composition here mangles the edges of the initial wound past the point of healing.

09 July 2010

#83 of 2010: The Curse of the Cat People

"Oh Kay, we're gonna do the short, short version":

Mr. Golly Gee/Dad (still attached to spurned, cursed dead wife) has effectively domesticated his former office buddy/new wife, or she has domesticated herself to the point that you wouldn't know anything about her past life as a working gal if you hadn't seen the previous film. They have an imaginative and solitary daughter, Amy, and in raising her, Dad takes his characteristically simplistic approach (play with other kids = happily normalized life, tell me what i want to hear = i've taught you a lesson, incredible truths = lies). There's a somewhat underdeveloped and maudlin interwoven storyline about an aging actress (with something akin to alzheimer's) and the daughter who struggles to care for her. Simone Simon is as charming as ever, and her singing to/interaction with Amy is a highlight of the story, alongside the young character's personality and openness to the world. The plot climax during a blizzard on christmas is a bit too much.

21 June 2010

#82 of 2010: Cat People

"Cat People" has a lot in common with "I Walked With a Zombie" in terms of its ambiguity about what is really going on here. Both films utilize the exotic foreignness of non-American legend as a portal into the "unknown" and cross-examine seemingly supernatural phenomena (which is rarely evidenced visually) with the opinions of psychologists or doctors, and it is the viewer hirself who must ultimately judge whether disturbed minds or demonic curses are to blame for the trouble that transpires. In addition to ethnic and religious differences, "Cat People" also deals rather thoughtfully with the problem of defining love, as the storyline absolutely demolishes the lead male's simplistic ideals concerning the subject. So it goes like this: there are two beautiful, charming, decent women in the story. One is the delicate, dark (but still generally cutesy), sexually abstinent wife who possesses an undeniable, almost primal magnetism. The other is a peppy, self-assured office buddy who shares professional interests and skills (designing/engineering ships) with Mr. Golly Gee. After his marriage based on "I love you and you love me, even though I'm totally dismissive of your deeply held and life-guiding beliefs", he finds that (surprise) he's unhappy for the first time in his life- the bulk of which he describes as a happy childhood plus a great time at school plus lots of fun at the office. At this point is the scene during which office pal both describes a more solid (though still pretty idealistic) view of love and complicates the idea by professing the relationship between them to be a perfect example of it, but concluding the conversation without seeming to want anything decidedly romantic from him. I knew better than to get too hopeful about what a film made in 1942 might have to say about cross-gender friendships or acceptable gender relations, but (ultimate conclusions aside) "Cat People" was willing to engage the topic interestingly, and often in a way that demonstrated the weaknesses in patriarchal assumptions. I haven't even gone into the best part of the movie where the wife is following the office buddy down the street in the dark, but you gotta see it so WATCH THIS MOVIE.

17 June 2010

#81 of 2010: Dear Wendy

most of the reviews you'll find of this are negative in one of two ways: either they rip the movie apart for being absurd and unfollowable, or they seem not to mind the movie except for the "obvious" loathing of America and Americans which all Lars Von Trier's creative output (supposedly) seeks to exude. a few see it as more complex, and i'll side with them as far as the first hour and five minutes is concerned. during that time, this whole "pacifism with guns" thing plays out interestingly, confusing in its paradoxical theory and clearly unsustainable as a way of life. plenty of narrative details are left out the whole way through, but other embellishments (mainly velvet or pearl or wood) are inserted in their place, and as all of the rising actions occur- the kids become truly happy in their committed (and impressively academic) pursuits, their concealed weaponry maximizes their confidence as worthwhile members of a dead-end society, their parents die off of apparently unimportant natural causes- everything looks nice enough, is fanciful enough, and develops a style enough to hold your attention. beware the dreaded plot climax. of course it's a showdown. how could it not be a showdown. but the premise for the shoot out with the law is completely brainless. built on a foundation of a few lines of shitty dialogue (it isn't Danso Gordon's fault that his character was saddled with being the bridge from "secret good times with friends and guns" to "fire-away suicide mission to deliver some coffee"), the scene that allows for the guns to "awaken" and serve their destructive purpose never tries to defend the protagonists' hitherto good-heartedness. the first kill has no discernible motivation beyond shutting up an annoying adult, which completely destroys any affinity i had for the kids. you can go back and forth all you want about whether or not this is satire, who is being caricatured, if Lars Von Trier makes movies exclusively to try and trick Americans into paying to see themselves made fun of (I don't feel like a target here, but apparently some people do? maybe the ones who have managed to befriend only named revolvers?). the way i judge a movie is by how well it holds together, how skillfully it does its own thing. this one disintegrated as it tried to figure out if it said that out loud or just thought it. watch it until 1:05:08, then turn it off and make up your own ending. and P.S.: you did a pretty good job, Mr. Vinterberg. the writing sucked way more than the things i feel like you had control over.

15 June 2010

#80 of 2010: Moon

Sam Rockwell is, in general, fun to watch. The retro effects and costuming combine with the binary scenery (in the base or in the rover outside the base) and "British" filming to give the film a "walking with dinosaurs" style documentary kind of look into a time we can't see photographic evidence of. "Moon" is like a dramatization of the future, a recreation of what happens years from now, when the line between valuable life and expendable life rests in a different place than it does now (currently, corporations allow oil rig employees to blow up because safety hampers production. in the future that kind of abuse might be a little more flagrant). yea, the story wasn't air-tight. if it had been weightier, more emotionally demanding, i would have taken issue with the glaring moments of "nah-ah, no way". but the film was mostly sweet or funny or thoughtful rather than epic or conscience-shaking or heart-rending. its axe grinding was more akin to the main character's whittling (versus the extreme display of corporate greed in, say, "District 9"): it's not all that detailed, it simply beats sitting on your ass and forgetting about life's finer print (that is, what actually makes it matter, which people profess to care about, though not enough to read into it too deeply). what i mean is, Jones and Parker sort of indict LUNAR inc., but the story is more about being a human- and the "sarang" (the name of the base which i learned from wikipedia means "love" in Korean) that defines us, whether clones from a common source or simply fellow members of the species- than fighting "the man", or even picking out an "evil" "the man" to fight. "Moon" doesn't point fingers or seek violent comeuppance, it quietly asks us to consider the question of the opening credits: "where are we now ?" on the timeline that leads to the future depicted here.

#79 of 2010: Hunger

i'm tempted not to say a whole lot about this. one reason is that i still can't be absolutely sure that it streamed correctly. but i'm fairly certain it did, so what i do say will be based on what i saw/heard (and didn't hear). most of the movie i saw was silent. if not silent, it was muffled except for the choice mic-ing of wood being shattered and water being splashed, etc. this may be what one critic meant by complaining about the film coming off as "scrubbed of political dialogue" or something to that effect. but the visuals were so audible, and the near-absence of "civilized sounds" like talking or music makes the minute or so of violin (beginning at minute 28:49) the most expressive audio possible at that moment in the film. also, any kind of vague politics or selectively-contextualized fault gets quickly re-embodied in individuals when nothing about those individuals is conveniently explained.

another reason that i don't want to say a whole lot is that this guy- http://www.donalforeman.com/blog/?cat=2 - already has, and i think you should read it. you should also see "Hunger" for yourself.

#78 of 2010: The Notorious Landlady

first and foremost, i was surprised to find Jack Lemmon carrying himself more gracefully than Fred Astaire (who i kept wishing would break into a fit of irrepressible tap-dancing, but alas. . .). oh man, that scene where Jack's going downstairs to snoop around or get the scoop after he hears something, and down an entire flight of stairs his hunched shoulders and lowered brow both stay perfectly level, perfectly parallel to the floor. he just glides around. what a charmer. people (including me) say that the best actors aren't the drama mongers, the best actors are often the truly funny comedians. maybe they're the best dancers, too. Kim Novak was enchanting except for when she clung to Jack and bobbed her head and flung her eyebrows impossibly high, all alternately, robotically, and to some horrible rhythm. that was hard to watch, but it was over in a matter of seconds and she was her same slick, wide-faced whisperer once again. The crazy camera angles and light-speed panning and zooming at the moment of the movie-opening murder were notable, as was the coherence of the plot-driving mystery's resolution. it's a sexy romp and a sizzling suspense and might even be considered female-empowering. and if for no other reason, watch it because the guy who plays officer Oliphant is so. spot. on.

13 June 2010

#77 of 2010: Cria Cuervos

like "spirit of the beehive", "cria cuervos" is a movie about pivotal events during childhood, stars Ana Torrent as the central character, and allows children to be complex and/or uncomfortably (though realistically) amoral. the later film also echoes the earlier in the way that it treats fascism and political turmoil as secondary to the more immediate experiences of family life, but makes sure to demonstrate a strong connection between the socio-political situation of the time and the behavior of the adult characters, which in turn seems to offer insight into the behavior of the children. one thing I could have done without was the flash-forward adult Ana appearing on screen in several highly contrived scenes (she is basically a speaking bust that seems to be answering the unasked question "what was your childhood like?") where she explains how she felt at age nine. this could have been included to introduce some instability into the narrative, call into question what we've seen. after all, if the movie is taken as the telling of memories by the adult Ana, we can assume that a good deal of it is confabulation, and that would somewhat explain scenes like the strange mash-ups of arguments between parents, where the girl Ana circles and observes in a way that tells us that the scene is not literal, not meant to be understood as "what happened", and that the camera is not acting as a witness, but as a "mind's eye". still, i feel that the subjectivity of the visuals- the fact that we are meant to see the movie as a look into Ana's mind- was clear without the adult version applying her overarching conclusions retroactively. it might have simply been the lines in these scenes that i didn't care for, or the fact that a woman staring into a camera as if she is being interviewed by a psychologist (who happens to be more interested in studying What People Say About Childhood than Childhood Itself) is not as visually stimulating as seeing what a little girl thinks. regardless, the movie as a whole is a successful (moving, articulate, beautiful) argument for the differentiation between inexperience and innocence. watch it, and relish "porque te vas".

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)